Leadership is a critical theme in both secular and biblical contexts. What distinguishes a leader from one who uplifts and one who destroys? The Bible offers profound insights into this question, particularly through the stories of women who either misused or embraced their power. By examining these narratives, we can gain a deeper understanding of how women can embody true leadership, contrasting the attitudes of entitlement with those of empowerment.

Entitled Leadership: Misusing Authority and Power

Entitled leaders often wield their authority like a weapon, leaving a trail of harm in their wake. This misuse of power is marked by arrogance, self-centeredness, and a disregard for the well-being of others. The Bible warns against such attitudes, illustrating the pitfalls of entitled leadership through various examples.

Key Biblical Examples:

1. Jezebel (1 Kings 16-21): Queen Jezebel is one of the most prominent examples of entitled leadership in the Bible. She used her position and influence to promote idolatry, orchestrate the murder of Naboth to seize his vineyard, and oppose God’s prophets. In today’s context, Jezebel’s misuse of power can be seen in leaders who prioritize personal gain over the welfare of their people or communities, leading to toxic environments.

SR ANJALA LINCY CLARK FSPM

To read the entire article, click Subscribe

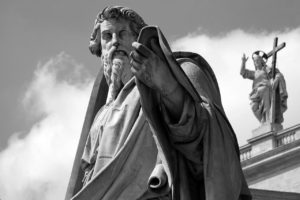

The Synoptic Gospels – Matthew, Mark and Luke – focused on the use of the term apostles for the Twelve or the disciples who accompanied Jesus during his earthly ministry and witnessed the resurrection. Luke, who employed the term more frequently than the other evangelists, also used the term apostle to denote someone fully authorized to represent the person on whose behalf the envoy comes or to be a witness to the claim of the one who sends. The same meaning is implied in the sending of the disciples by Jesus and the delegation of Barnabas and Paul by the Church of Antioch.

The Synoptic Gospels – Matthew, Mark and Luke – focused on the use of the term apostles for the Twelve or the disciples who accompanied Jesus during his earthly ministry and witnessed the resurrection. Luke, who employed the term more frequently than the other evangelists, also used the term apostle to denote someone fully authorized to represent the person on whose behalf the envoy comes or to be a witness to the claim of the one who sends. The same meaning is implied in the sending of the disciples by Jesus and the delegation of Barnabas and Paul by the Church of Antioch.